|

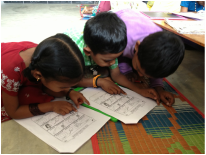

On a recent visit to the reputed Rishi Valley school in rural Andhra Pradesh, India (past posts on the philosophy of Rishi Valley here, and here) two friends and I had the chance to visit a rural school operated by Rishi Valley, under the banner “RIVER” (Rishi Valley Institute for Educational Resources). This one room schoolhouse typically housed kids aged 4 to 10, one main teacher, and one assistant. Students sat on the floor, with large square work tables a foot or so off the ground.  A path for students to follow their progress in math A path for students to follow their progress in math The teacher sat with students, patiently explaining concepts one on one, or in small groups. Surprisingly, kids at other tables quietly worked away without needing the constant attention of the teacher. Some would come to the front of the class on their own, checking a snakes-and-ladders type mural with a series of symbols that guided them into the next workbook or concept in math or Telegu (the local language). Seeing us arrive, students excitedly yelled out “Akka! Akka!” (older sister), showing off their work with big smiles.  local materials to help scaffold learning local materials to help scaffold learning I have seen several poorly-resourced classes in India and Uganda, and this one was the first to really impress me in it's programming. Kids of all ranges paying attention in a rural school, and being self-motivated?! What was going on in this classroom? How can we apply this elsewhere? What we observed at RIVER was part of a program called “Multi-grade, Multi-level" (MGML) teaching, developed by a few senior teachers at the larger Rishi Valley School. With the constraints of one teacher (and one assistant) across grades and across levels within each grade, the program works to help students take ownership of their learning, while allowing them to move at their own pace and not get caught up with comparing to or competing with other kids. The teacher introduces concepts to each student based on the level they are at (for example, kids learning basic numbers are given props such as bottle caps or chalk pieces to visually play with and match the number of objects to the numbers drawn on the classroom floor; as they move up in levels, they write out the numbers themselves, then move into addition, with the physical objects helping to scaffold their learning).  Working with the students - at their level! Working with the students - at their level! Some of these techniques may be used in elementary schools here and in other places, but to see them effectively employed in a school where resources are so limited (using local materials like bottle caps and stones) was impressive. This school has now become a model for other rural schools and government officials across India, offering tools and training materials to spread these techniques. Multi-grade classrooms are not unique to rural India. In fact, here in Canada, some alternative schools (without the resource issue!) are using this method so that students benefit from the learning and mentorship that happens between different age groups. I hope to explore more of these models in future posts.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

AuthorA passionate educator.. on a quest for a schooling model to love! Archives

August 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed